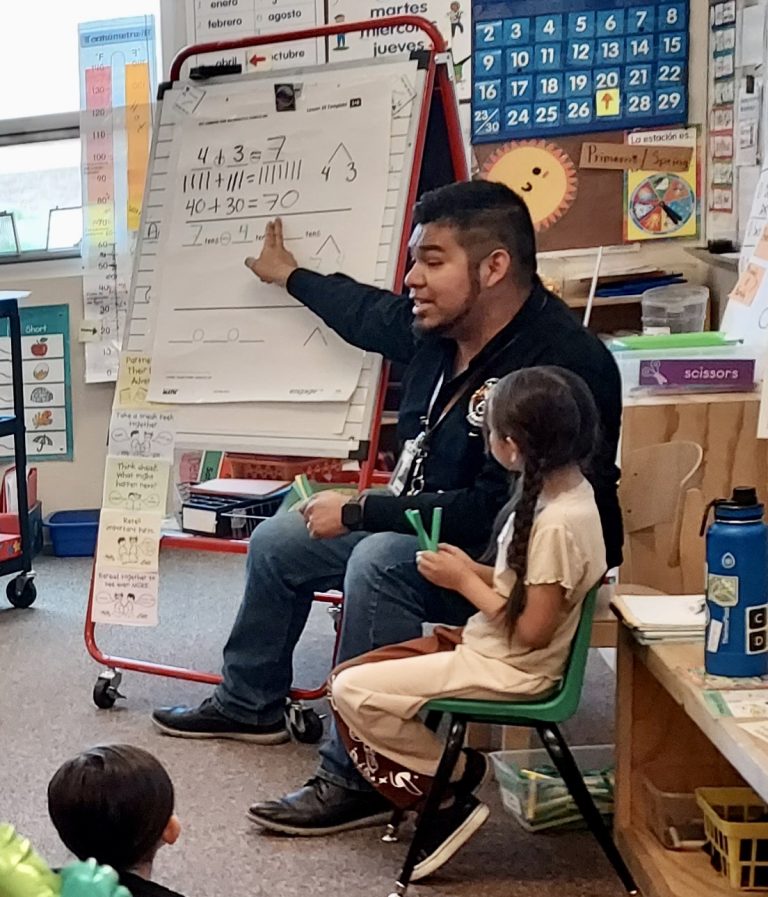

When you walk into Maxine Ortiz’s science classroom at Hernandez Elementary School in the Española Valley Public School District, you see posters on the walls, charts of collected data, experiential materials neatly on display, tabletops with results from ongoing experiments, students moving around the room and lots of discussion.

The room is busy and sometimes loud, but Ms. Ortiz says, “I’d have it no other way.”

She knows that with the ISEC (Inquiry Science Education Consortium) program’s free hands-on learning materials and rigorous, standards-based curriculum, her students are engaged and not just learning science but experiencing it. They become scientists who make observations, collect data, draw conclusions and reference past explorations and knowledge that they gain from lesson to lesson, grade to grade. Ms. Ortiz teaches 4th, 5th and 6th grade science and math and has a separate classroom dedicated to each subject. She often has the opportunity to combine both subjects in the learning process.

Her 6th grade class conducted an Earth History lesson that involves understanding natural phenomena related to geologic history using the Grand Canyon as an example. Students study at a map of the Colorado Plateau that spans parts of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah and Colorado and look at a large poster of the Grand Canyon.

“What land formations can you see in the picture?” she asks her class.

Students point out the layers of rock, the changing colors, plateaus, and mesas similar to what they have seen in the New Mexico landscape. They compare the way the Rio Grande carved out the Earth over time and created local canyons similar to the Colorado River that formed the Grand Canyon on a much larger scale.

Ms. Ortiz introduces the focus question that will guide the lesson, “How do Earth’s materials get sorted in nature?” She asks the class what are some of the things in nature that affect erosions. Heat, rivers, rain, wind, dry air and floods are some of the answers her students give.

“It took millions of years to form the Grand Canyon, but we don’t have that much time,” she said. “So we use a model to represent it.”

The class sets up a stream table that includes a tray that is partially packed with a soil mixture and a water source. Ms. Ortiz asks her students to surround the setup and observe what happens when she turns on the water to create a river in the model. Next, drops of dye are added in the water’s path to more vividly show the movement of the different materials.

She engages the students with more questions. “Can you see a canyon starting to form? What else do you see?”

Referencing their student guide, many other landforms are recognized on the stream table.

“There’s a delta and a canyon.”

”I see a plateau or a butte.”

“The water is pushing the sand and separating it.

“There’s a pool forming, and it looks like there’s a waterfall.”

“There’s a little island and a meander in the river.”

After the observations, the students draw a model of where different materials like sand and clay are being deposited along the path of the river. They note the landforms they came across and where changes occur in the water’s speed.

“It’s your labeling that matters, please use correct spelling,” Ms. Ortiz reminds the class. “If you don’t label your diagram, we don’t know what’s going on.”

In small groups at their tables, students compare their drawings and discuss individual observations.

Afterward, the entire class gathers in a standing meaning making circle and further reflects on their experience using the focus question again as their guide.

They discuss what the stream table looked like when the water first was added and how that changed over time. They pointed out how fast the water moved at different stages and how adding the dye was an important way to show where the water goes, how fast it moved, and here materials were deposited.

“The force of the water pushed the sand and clay. It created erosion.“

“After a while, it made more than one stream.”

“I think I saw a caldera starting to form,” said one student.

“I disagree,” said another. “A caldera is made by a volcano not water.”

Ms. Ortiz has been teaching for 14 years, was a principal for 9, and has spent 4 years at Hernandez Elementary using the ISEC science kits, curriculum and taking part in teacher training provided by the LANL Foundation. She has seen the impact this kind of science instruction has on her students.

“The hands-on activities are great, they really love the rocks and soil,” she said. “They’re engaged and doing the writing, and I loved that.”

Every other Friday, Ms. Ortiz also brings another area of science to her 6th grade class. She teaches robotics with the help of five mentors who are college students from Northern New Mexico College, right down the road from Hernandez.

When the class is asked what they like about science and the exploratory activities, the enthusiasm is clear. “Everything. It’s fun, and we can get our hands dirty.”

LANL Foundation’s ISEC Program Manager Bryan Maestas grew up nearby and attended Hernandez Elementary. He says that if he had experiential activities and was allowed to get his hands dirty at this age, it would have been a game changer. He’s happy to bring the program to thousands of students throughout Northern New Mexico and see how excited and engaged they are in science.