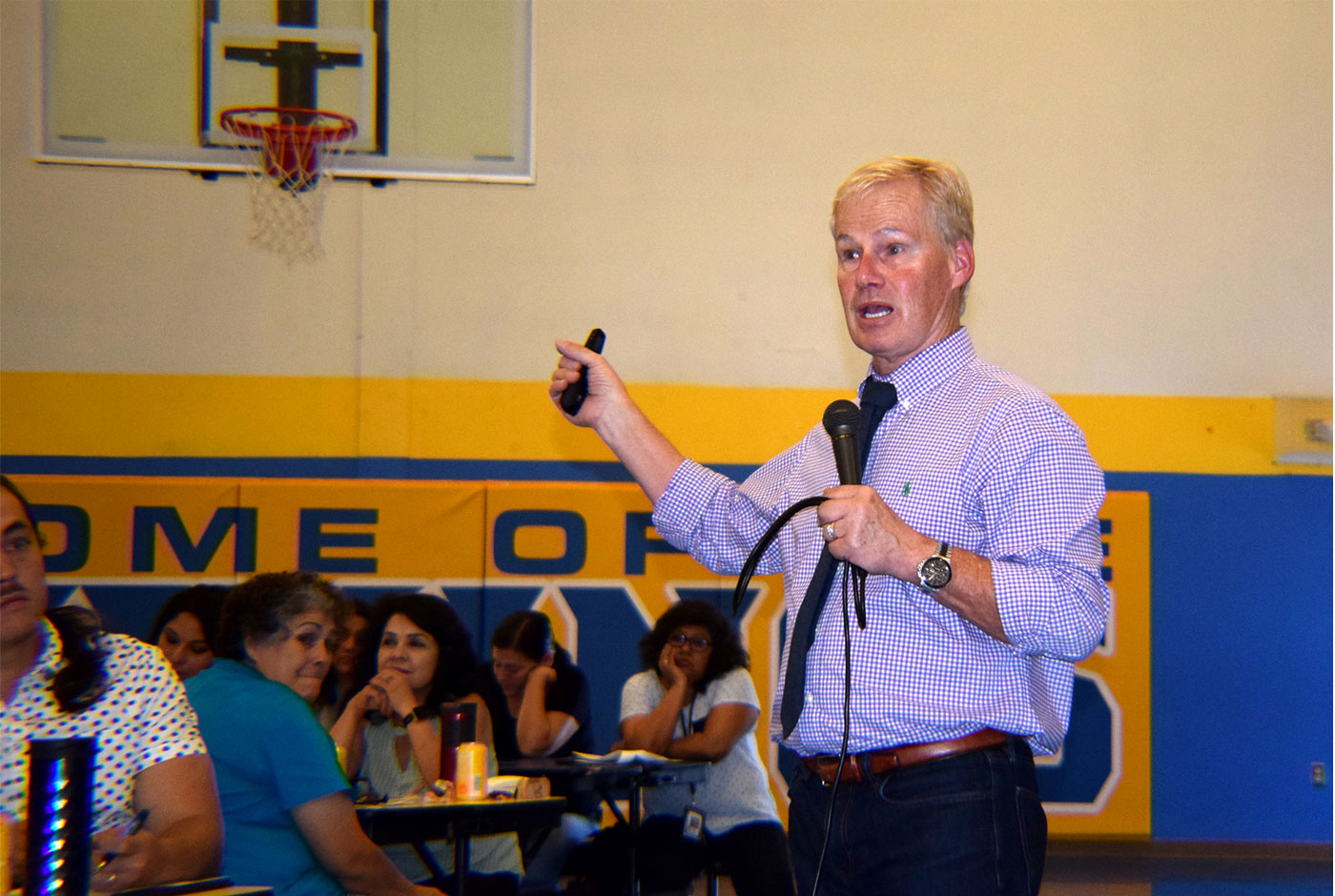

Southwest Family Guidance Center and Institute Founder & CEO Craig Pierce led a workshop on understanding how trauma interrupts brain development in children and how to work with traumatized students in the classroom.

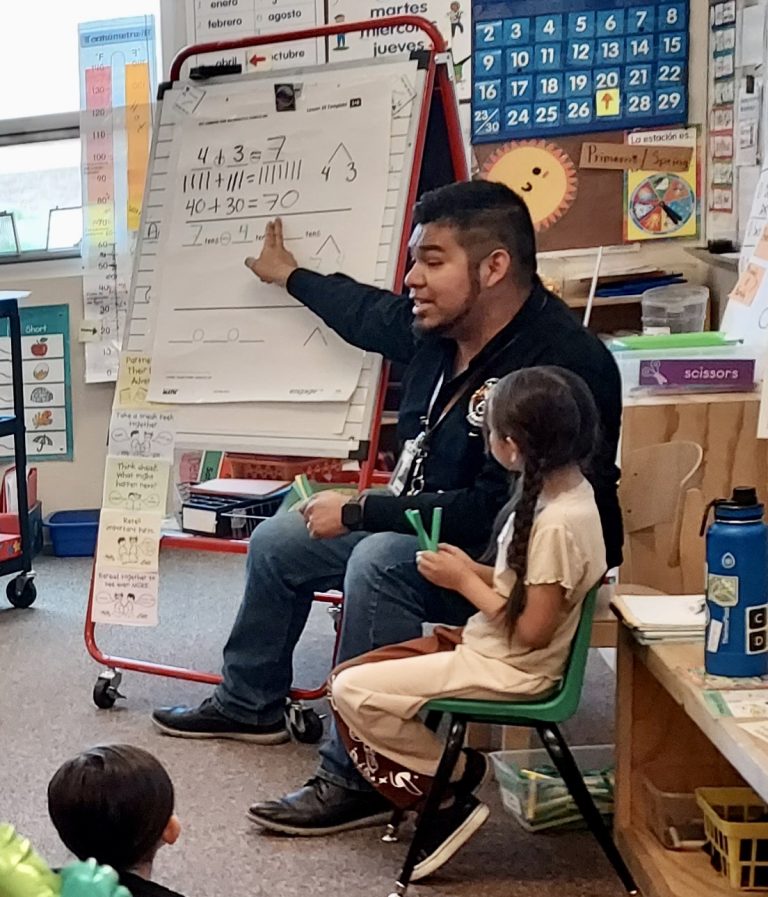

LANL Foundation is committed to preparing and supporting local educators and focusing on whole-student development. In alignment with this priority, teachers and staff from five Española Public School District elementary schools were offered Thriving Students training at Tony E. Quintana Elementary School on Sept. 11, 2019.

The session was presented by Southwest Family Guidance Center Institute’s founder and CEO Craig Pierce, PhD, LMFT, LPCC. Pierce is a leading expert in trauma-informed treatment with more than 30 years of experience as a clinical counselor and family therapist.

“Our goal is to change the negative trajectory of failure and exclusion to create school cultures that inspire success and inclusion,” Pierce told participants. “I want you to shift your perspectives of how we view kids and the families that they come from and the challenges that they bring us. You are in one of the most powerful positions to change the trajectory for a child and their family.”

Tony E. Quintana Elementary School Principal Sherri Rodriguez welcomes teachers to the workshop.

Funded by a $25,200 grant from the LANL Foundation, the training was part of a Social Emotional Learning (SEL) pilot program for educators in James H. Rodriquez, Eutimio T. Salazar, Chimayo, Tony E. Quintana and Abiquiu elementary schools. SEL is recognized as a primary focus area in the Foundation’s K–12 Program. New Mexico Public Education Department’s (NMPED) Health & Wellness Standards also require schools to provide SEL tools and resources. Thriving Students is an effective SEL professional development program that connects school staff with strategies to tailor trauma-informed support systems for students.

New Mexico ranks as 49th in the U.S. in education, and the solutions tried so far have been ineffective. Many New Mexico children are testing behind their peers in reading and math as early as the second grade.

“At face value, that makes it look like teachers and educators just plain are no good, but it is the furthest from the truth,” Pierce said. “The reason we’re number 49 is because we’re number 50 in child wellbeing. If wellbeing is positive, you’re going to get more achievement. Wellbeing and achievement go hand in hand.”

Pierce noted that New Mexico has one of the highest per capita rates of children living below the poverty line, the highest rate of substantiated child abuse in the country and that 60 percent of the parents who neglect or abuse their children have a significant substance abuse issue, well above the national average of 20 percent.

“Keep in mind that you’re dealing with some of the most challenged kids and families, and in spite of those challenges, they’re still doing well,” Pierce said, while urging educators not to be discouraged by low test scores.

According to Pierce, the traditional response to low test scores skips a step by jumping immediately to, “What do we do about it?” instead of asking, “Why are so many kids already behind by the second grade?” Past solutions have been to intensify teacher evaluations and increase testing, which did not significantly improve test scores and drove good teachers out of the local schools or the profession as a whole.

“With greater wellbeing comes a greater sense of social emotional skills to go with the academic skills, regulation, getting along with other kids, being able to feel safe. Until a child’s in a state of wellbeing, achievement’s not going to follow because they’re not in a state of mind to learn.”

The teachers and staff were challenged to ask themselves “How am I showing up?” Are they mindful or just going through the motions, with curiosity or with a closed mind and pessimism toward students, and do believe they can have a positive outcome with difficult students? He asked if they are open to learning about the stresses the student is facing at home and changing their paradigm of approach.

“I believe wholeheartedly every child that you’re challenged by wants to do better. And I hope that you believe that, because as they present themselves oppositionally, reactively, defiantly, they act like they don’t care,” Pierce said. “How can we support them to more optimally function? You are in a powerful position to inspire success and inclusion, and when we are successful and included and connected, we can achieve in any part of our lives.”

Pierce described how trauma and lack of positive, consistent relationships impact a child’s development. He cited Dr. Bruce Perry, who says that the brain of a child will become exactly what it’s exposed to.

“A lot of our children weren’t exposed to what they need to develop the part of the brain and skills for the challenges that they’re facing,” Pierce said. “We’re born with the capacity for language, but in order to speak a language, we have to be exposed over and over in a very consistent way to that language. That is no different the social emotional part, the empathy part, the self-regulation part, the reward part of our brain. We have to have positive experiences in a predictable, repetitive way in order to develop that part of the brain.”

A traumatized child can enter kindergarten with only half the developmental capacity of other children their age. Without intervention, that child will continue to function far below his expected capacity as he moves through each grade level.

“The teacher expects a child to function socially, emotionally, academically like a five-year-old, but the truth is, he’s about a two-and-a-half-year-old on most levels,” Pierce said. “Would you put a two-and-a-half-year-old in kindergarten and expect them to function?”

Teachers from five Española Valley Public Schools involved in the Thriving Students pilot program gather in the Tony E. Quintana Elementary School gymnasium for a workshop with Southwest Family Guidance Center and Institute: Founder & CEO Craig Pierce.

The Thriving Students program offers a framework to help educators work with their challenging students by moving away from punitive and authoritative actions to developing safe, empathetic relationships. Educators learned about positive framing and not dwelling on the problem, but instead naming the issue then focusing attention on where they want the student to go, what skills the student needs and how acquire them.

“Always focus on what you want and what you can provide for them to do better,” Pierce said. “We need to look through the eyes of, ‘What do you need?’ ‘What’s happened to you?’ not ‘What’s wrong with you?’”

The goal is to help the child reach normal functioning by providing consistent experiences that grow the underdeveloped parts of the brain. Pierce encouraged that this is possible regardless of a child’s history.

As follow-up, a facilitator will provide targeted training for a Core Team at each school, helping them create a detailed Thriving Student plan for selected students, with 16 weeks of ongoing coaching to guide and refine individual plans. This ongoing instruction will empower teachers, school counselors and administration with skills they can continue to develop and implement. Data will be collected at the end of the year with a survey given to the school counselor and key administration to measure the program’s effectiveness.