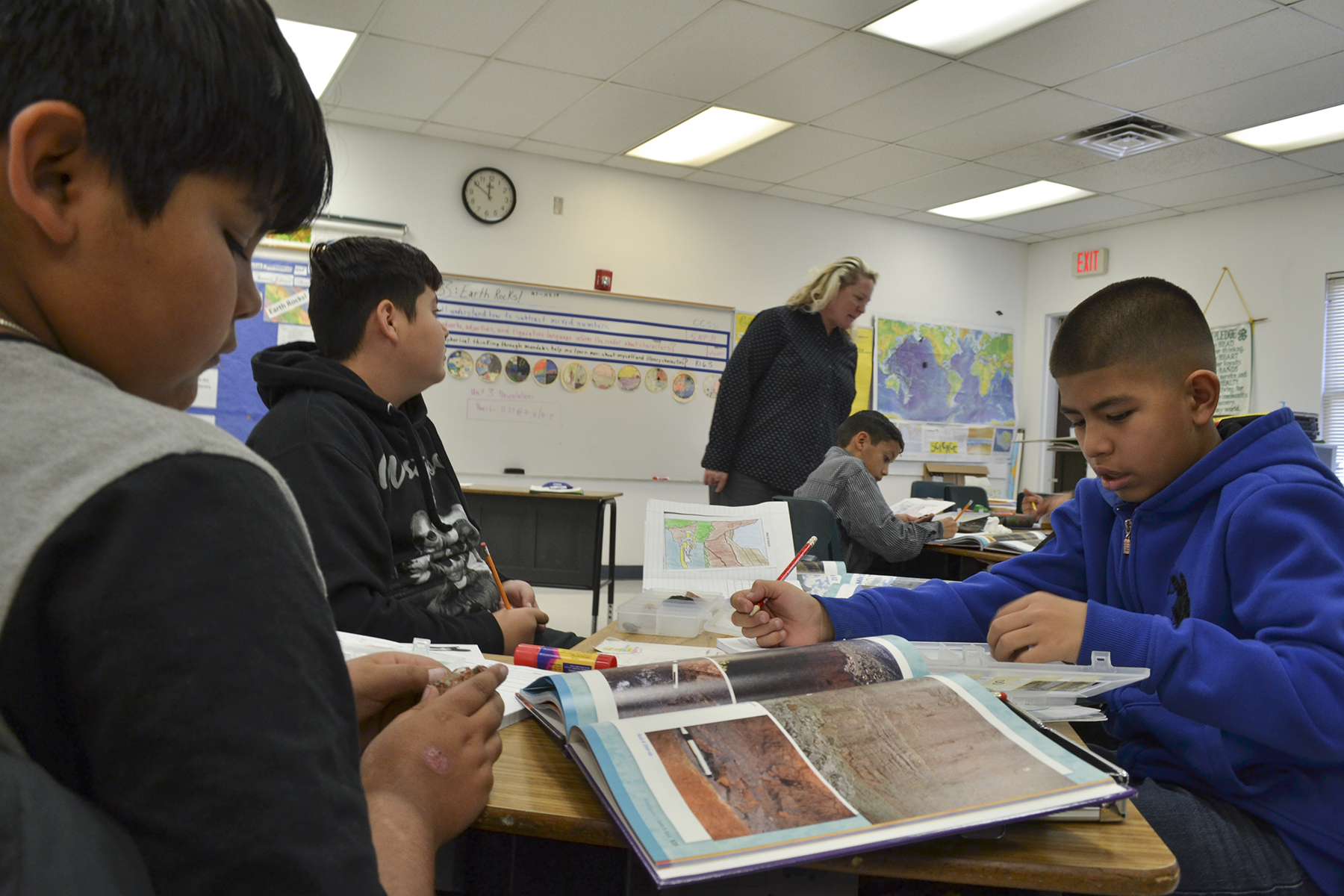

Janan Talmadge’s students are bursting with excitement for their Grand Canyon, Earth is Rock investigation in ISEC’s 6th grade Earth History kit. “We’re going to test rocks with acid!” exclaims Carlos Rascon-Bencomo, one of Ms. Talmadge’s 5th grade students.

Velarde Elementary has just over 60 students, so small classrooms are combined like Ms. Talmadge’s 5th and 6th grade class. She alternates grade-specific kits, with this year focusing on the 6th grade curriculum. Ms. Talmadge has amped up the lesson, calling it “Earth Rocks!” ISEC engendered her love of science, which is evident as she leads students through the lesson. They respond to that enthusiasm.

“With science, it’s like discovering something for the first time. Science is inquiry, science is wonder, science is, ‘Oh, my gosh, I’ve just discovered that,’” Talmadge said. “ISEC reinforces that love of science: to always have that inquiry, to always inspire kids to wonder why, how, what if.”

The students must hold their eagerness for experimentation in check while they engage in the preliminary exploration. Their role model is Major John Wesley Powell and his famous 1869 expedition through the Grand Canyon on the Colorado River.

The focus question is “Why do there appear to be stripes on the walls of the Grand Canyon?” Using photographs from the textbook, rock samples and science notebooks, the students act as geologists mirroring Powell’s journal observations of the canyon’s terrain and cataloging of rock samples, which aligns seamlessly with Next Generation Science Standards. Ms. Talmadge tells them, “You guys are like mini Powells.”

The students model the canyon walls by coloring the sedimentary rock layers in a landform seen at either Mile Marker 20 or 52 along the river. Ms. Talmadge asks them to “dig down deep” to figure out why the stripes are there and what that tells them about the story of the Grand Canyon.

Next, they collect data about color, texture and size of rock samples and record observations. Using the photos, they “correlate” (one of this lesson’s vocabulary words) the rock with its layer in the canyon wall. They venture further into scientific inquiry, exploring the question, “What does this rock make you wonder?”

Students working on Mile Marker 20 grow excited when they find fossils in rock #10. Carlos is the first to make this discovery and formulate a hypothesis. He tells Ms. Talmadge, “I wonder if the mud got collapsed with the seashell in the flooding in the Grand Canyon that you told us about, which actually made this.”

The classroom hums with dialogue as the students share discoveries in small groups and collaborate to identify rock characteristics. One student exclaims that the rock he is exploring feels like sandpaper.

Ms. Talmadge calls the students together for a Meaning Making Circle to share observations and respond to the focus question. Ms. Talmadge reminds them how they can agree with someone and add another observation or “respectfully disagree” and share an alternative view.

In the circle, Carlos further refined his hypothesis. “What I observed about this rock #10 is that it has fossils,” he says. “That tells us that there was an ocean right there.”

Another student was working with rock #5 from Mile Marker 52. “What I observed about my rock sample is that it has markings that look like petroglyphs on three corners of the rock.”

Ms. Talmadge then asks students from one Mile Marker group to pair with someone from the other group to share discoveries about the rocks they’ve been exploring, giving every student the chance to participate in the discussion.

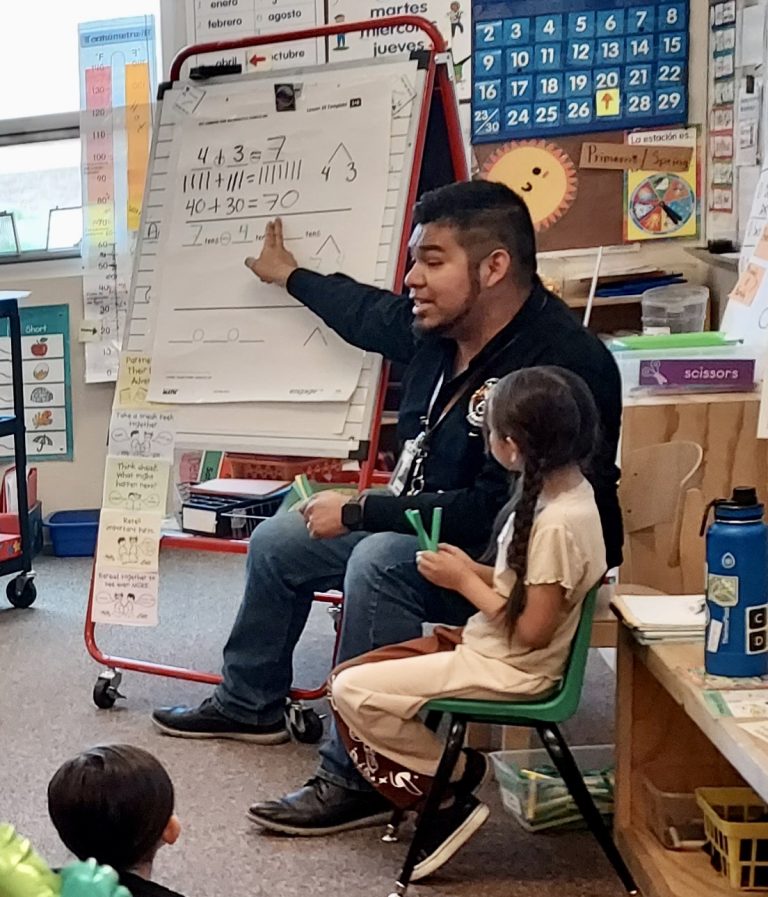

Carlos and the other students must practice patience a little longer. They won’t get to do the acid test until the next lesson. Once the three-part investigation is complete, students will pair up with a younger student to develop presentations based on the kit’s projects, which the entire school and parents are invited to attend. Teaching others demonstrates that the students have mastered the content. The presentations also help them develop communication skills and support social emotional learning by boosting their self-esteem in front of their peers.

Beyond Science: Using ISEC for Project-based Learning

As an 11-year veteran educator, Ms. Talmadge attributes her success in the classroom to engaging and exciting students’ through the inquiry process and her “dash of dork.” Her dedication to the kids and teaching profession is clear. She is a member of ISEC’s select Teacher Leader Cadre and trained her peers at the summer Teachers’ Institute. She is also in the rigorous process to become a National Board Certified Teacher (NBCT) with support funded by LANL Foundation and Triad National Security.

Ms. Talmadge goes the extra mile, investing time and effort to develop project-based learning opportunities using science as the vehicle to pique students’ interest. She aligned English Language Arts with Earth science through writing assignments and having the class read Downriver by Will Hobbs, a novel that chronicles a group of teens on a wilderness therapy adventure through the Grand Canyon. A local river guide and wilderness therapy counselor spoke to the class, and students were asked to take a stance about the efficacy of wilderness therapy and write a persuasive essay supporting their position. Their arguments were used in a pro/con debate.

As an art extension, students will create Grand Canyon dioramas. They will also design a mandala that reflects the duality of human nature through a character in Downriver. While metaphorical thinking in this activity may be considered too advanced for this age, Ms. Talmadge believes otherwise. She shares her favorite quote displayed in her classroom, “My teacher thought I was smarter than I was, so I was.”

Every aspect of the project-based curriculum, including the custom rubric and performance assessments, meets Common Core requirements as well as New Mexico STEM Ready! Science Standards.

“With this integrated approach, they see how science is connected to all these things. They’ll never forget it,” Ms. Talmadge said. “Give the kids opportunity, they’ll blow your mind.”

Although project-based teaching requires more planning upfront, LANL Foundation’s K–12 Professional Development Coordinator Doris Rivera sees that integrated learning could help solve one of the most common education challenges she hears.

“Teachers feel like they don’t have time to teach all of the subjects and meet all of the expectations placed upon them,” Rivera said. “Teaching integrated content areas with several subjects all at once means that the class can cover more material, and the kids are excited and engaged in the process.”

The 4-H Connection

Ms. Talmadge also tied the ISEC investigation to the school’s 4-H theme of “Then and Now.” Velarde Elementary is the only 4-H school in the Española district, with core classes four days a week and 4-H activities on Fridays.

4-H donated wood so the class could build a replica of Powell’s boat, but the plan fell through when a student pointed out that a steam machine was needed to shape the wood. Instead, students are making soap carvings of Powell’s boat and contemporary river rafts. They will also dehydrate apples, which was one of the foods Powell’s team brought on their expedition.

The wood will be used to build a replica of Magellan’s boat for an upcoming social studies unit, then recycled to build a Conestoga wagon for their westward expansion studies and again to make a planter for herbs for Cooking with Kids. Through Ms. Talmadge’s project-based approach to teaching, fun integrated learning possibilities are endless.