Over the last year, Inquiry Science Education Consortium (ISEC) Professional Development (PD) Specialist Doris Rivera, PD Coordinator Danielle Gothie, and ISEC Program Manager David Call have spent time supporting teachers in Chama Valley Independent Schools, one of the districts in the latest cohort that started with the program in 2016–2017. The team of PD professionals have been co-teaching, co-planning, and reflecting on student-centered coaching alongside teachers to strengthen the inquiry process and student learning outcomes.

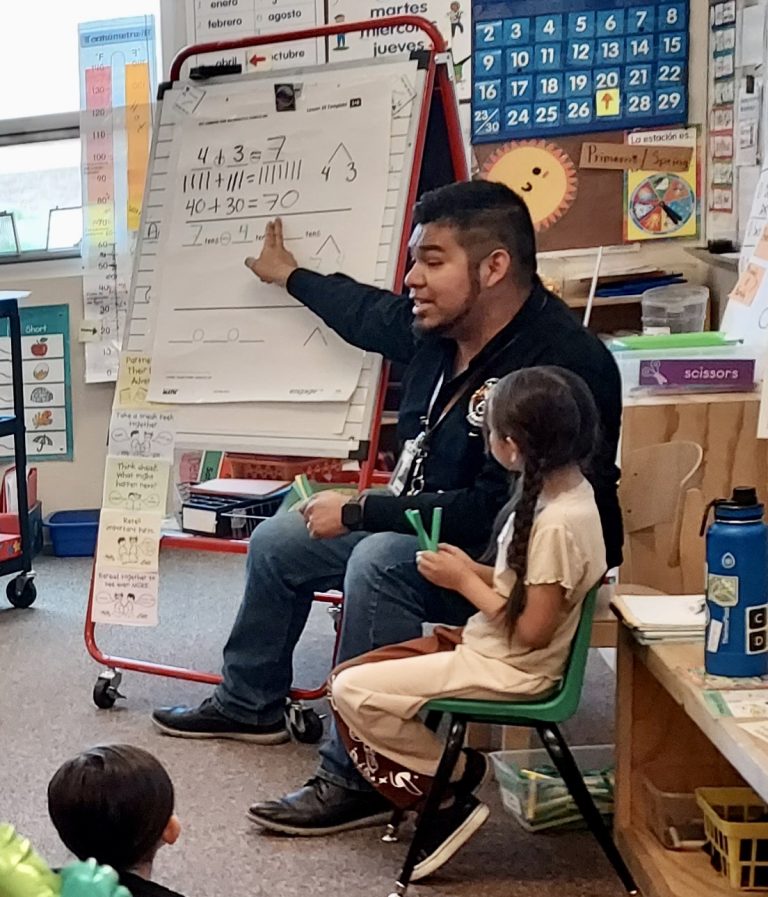

Cadie Carrillo and Myra Chavez are two of the star teachers at Tierra Amarilla Elementary School in the Chama district. Their strengths were revealed during recent visits to their classrooms.

Ms. Carrillo’s third grade class worked from the Water and Climate curriculum. In prior lessons, the class learned about states of matter, molecules, density, temperature, and measuring with thermometers.

“What happens when hot or cold water is put into room-temperature water?” asked Ms. Carrillo. This focus question frames the lesson and allows students to make predictions before the experiment takes place.

In small groups, the class conducted the experiment with small vial of red-colored hot water slowly lowered into a larger cup of room-temperature water. Another vial of blue-colored cold water was carefully placed in to a different cup of room-temperature water. The students observed movement in the water and colors.

“Take a minute to discuss with your group what happened with the cold water and the hot water.” After small group discussions, the whole class shared their observations.

(Above) Doris Rivera sits in on a lesson with Ms. Carrillo’s third grade class.

“The hot water went to the top of the cup,” said one student.

“What’s a word to describe that?” asked Ms. Carrillo.

“Float!” called out another young scientist.

“What about the blue water?”

“Blue water didn’t float as much as, because cold water moves more slowly,” was one observation.

“Blue water sank to the bottom of the cup,” another chimed in.

“Let’s talk about density. When things are more dense, what do they do?”

“They sink.”

“Less dense?”

“They float.”

“Right! So, which one is more dense, hot or cold water?”

“Cold!”

Students were asked to draw models in their science notebooks of what they saw and answer the focus question, using complete sentences and their new vocabulary. The following day’s lesson would begin with a meaning making circle with a deeper discussion of the experiment to synthesize what they learned.

Ms. Carrillo also teaches Kindergarten science from the Exploring My Weather curriculum. During one lesson she asked her class to review vocabulary words and remember the big, new word they recently learned. They talked about precipitation and revisited the four types: rain, hail sleet, and snow.

The class watched a video about weather, made observations, then were asked to write about precipitation. “What do you like about rain and snow? How do they feel?”

After quietly writing and asking for help with ideas and spelling, the Kindergarteners read their sentences aloud.

“The snow falls. Snow is cold. It is good for making igloos.”

“Snow is fluffy. Rain is wet.”

“I like to play with my sister in the snow. I like to play in the rain.”

Down the hall, Ms. Chavez’s first grade class was well into the Air & Weather curriculum module. The young researchers had already explored abstract ideas about air. Even though it is invisible, air is matter and has properties, it takes up space, and can be compressed.

The students’ eyes lit up when they saw balloons as one of the materials in their science experiment. The focus question, which Ms. Chavez asked her class to write in their science notebooks, gave a clue how the balloons would be use.

“How can compressed air be used to make a balloon rocket?”

The class talked about what a rocket is and how they are launched into space. With an air pump and counting the number of compressions, the students blew up a balloon. While holding the open end closed, they put the balloon filled with air into a zip bag attached to a straw with the stretched “flight line” of string threaded through.

Letting go of the balloon led to an exciting WHOOSH that pushed the bag along the string. The process was repeated and each time the students collected data on the number of air pumps into the balloon and the distance the rocket traveled.

Going back to the focus questions, Ms. Chavez asked the class to draw and label a model of the balloon rocket system. Afterward, with pride they took their notebooks to the carpet and sat in a meaning making circle to discuss their observations.

“You can compress air in the tube. We put air in the balloon to blow it up.”

“The air pump is pushing the air in to the balloon. When we let the balloon go, air comes out.”

“The air pushes the balloon and it flies.”

Ms. Chavez explained that the compressed air created pressure inside the balloon. When it is let go, the pressure is released, and the air goes out the opening, making the balloon and bag move along the string.

As a former teacher at T.A. Elementary School, Doris has enjoyed seeing her former students progress.

“Last class I taught was 3rd graders who are 6th graders there now. Best part is hearing success stories from the kids, like, ‘I had so much fun in your class’ or ‘I love science; we have so much fun’ or ‘you taught me how to read.’”

Now in her professional development and coaching role Doris sees the importance of recognizing and building upon strength in the teachers she supports.

“So much about coaching and effective teaching is awareness. Teachers are noticing things and have aha moments by knowing how to observe their own practice.”

Ms. Chavez highlights the value of the one-on-one focus she receives through coaching and the time she now takes for reflection. A key observation she made was that the third graders struggled with formulating questions.

“I noticed that the kids could make statements but couldn’t articulate a question. We broke it down, and I explained that a question starts with who, what, where, why, how, etc. Now that they are getting this, they can answer their questions. Their writing and how they structure sentences has improved so much. They already had the information in their brains, but now they are writing about it. It’s growth!”