What is it?

The Indigenous Science Initiative is a collaborative project between the NACA Inspired Schools Network (NISN) and the Los Alamos National Laboratory Foundation (LANL Foundation) with teacher-designers and community members to create an open access (freely accessible and online) science curriculum that centers Indigenous perspective and community values while also featuring inquiry learning, culturally sustaining pedagogies, and climate science through story, the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), and local context. The current version of the curriculum focuses on an approach to the middle grades – 6th, 7th, and 8th grade – with yearlong plans and four distinct units of instruction per grade level.

Why this curriculum? Why now?

Indigenous perspectives have always mattered and Indigenous peoples have practiced science since time immemorial. Western education systems have not historically elevated and centered nor included Indigenous perspectives in science education, let alone in education systems overall. In this day and age, our education systems need to reflect the diversity and beauty of all student backgrounds, including Indigenous students. Through this Initiative, we strive to demonstrate what is possible and a method for centering Indigenous Science and we intend to provide guidance for how to localize this approach across many different contexts. We believe that this work can be a part of a broader effort of “desettling expectations in science education” (Bang et al. 2013), represents a response to the findings of the Martinez-Yazzie Consolidated Case, and contributes to a more equitable public education system for all students.

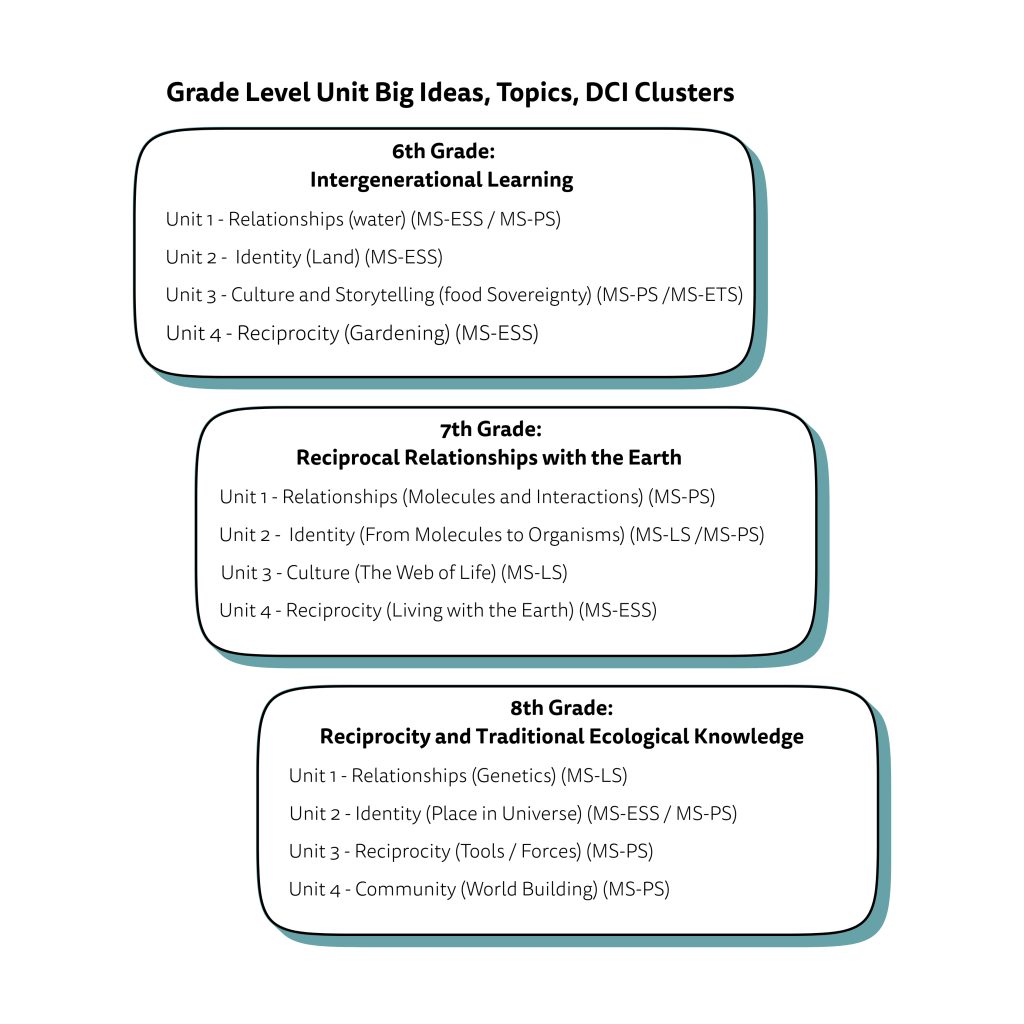

While each grade level sequence and unit is its own unique story, the graphic of grade level unit topics below highlights the big ideas in each grade level and unit. Teacher Designers have aligned their planning with the four big ideas of Relationships, Identity / Equity, Reciprocity, and Community/Culture, as well as the NGSS Disciplinary Core Idea (DCI) clusters.

When reading the grade level topics graphic below, please note that the unit titles are named in the following way: “Unit # – Unit Title – ISI Core Value – Next Generation Science Standards Disciplinary Core Idea Cluster” to share information about each unit in a shorthand way. A table is also included to provide more information about the DCI clusters.

Four Big Ideas: Through the curriculum design process and through intentional discussion with community members, teacher designers came to the following big ideas as being central to the Indigenous Science Initiative:

- Relationships:Everything is interdependent, forming a web of connections that cannot be separated, though we may often feel separate in contemporary times. There are deep interconnected relationships between people and the natural world, including land, water, plants, animals, and other beings. Awareness and respect for this interconnectedness is essential for understanding the complex ecosystem we are all a part of. Reflecting on Relationships through scientific inquiry helps us to understand concepts of interdependence, mutual reliance, and the interconnectedness of all things.

- Identity / Equity: The quote “Them? Us? They are us.” underscores the idea that there is a connection between knowing oneself – understanding and valuing one’s personality and culture – and recognizing the shared humanity in others in order to live in a way that brings respect to all beings. To engage with questions of Identity and Equity means to engage with themes of respect for language, culture, place, worldview, living in balance and the interconnectedness of ourselves, each other, and the world around us.

- Community / Culture:Community means many things to many people. Community can mean home, place, people, and context. It can be immediate or spread out over distance. This big idea came from frequent references to the idea of “community based” teaching and learning and the recognition of community as a central component of enduring learning in the Community Led Design discussions. The ideas of working together with shared respect and responsibility, sharing teachings, collaborating, and a shared sense of place are all connected to community. To be in community and to learn in community means to celebrate and value place, to recognize the many dimensions of place, and to see local places as necessary and essential to meaningful, enduring science learning.

- Reciprocity:Reciprocity is to be able to give and receive gifts in gratitude and recognition. It is like breathing and knowing the rhythms of the world. This includes caring for the environment and one another, with a grounding in the core values of respect, mindfulness, and interconnectedness, as well as a sense of care, understanding, and awareness, encouraging us to listen, pay attention, and thoughtfully consider our actions. Reciprocity calls for recognizing the importance of all forms of wildlife and human beings in preserving the environment, while honoring past, present, and future generations. By taking care of each other and being mindful of our impact, we create a reciprocal flow of giving and receiving that sustains both the environment and our relationships and ourselves.

Who is this curriculum for?

We envision the Indigenous Science Initiative being beneficial to students and teachers of all backgrounds. This curriculum seeks to center the perspectives and strengths of communities and is written with an eye towards what we call “localization,” or developing and adapting curriculum in partnership with community and according to community values, stories, beliefs, strengths, challenges, opportunities, and much more. In particular, we imagine users of this curriculum adapting and localizing the investigations to best fit their students, local contexts, and histories. We envision users of this curriculum, teachers and students alike, experiencing the curriculum as both a mirror into their life experiences and funds of knowledge as well as a window for developing a curiosity, respect, and understanding of the life experiences and funds of knowledge of others.

Core values and processes

There are several important processes and concepts that have guided the development of the Indigenous Science Initiative curriculum. Those processes and concepts include Indigenous Genius By Design, Community Led Design, Teachers as Designers, Four Big Ideas, and the long history of many different forms of Indigenous Teaching and Learning.

Indigenous Genius By Design (IGbD): A re-frame on the principles of backwards curriculum design created by NISN and used for original curriculum design, IGbD is a process and a tool used by the NACA Inspired Schools Network (NISN) and partners for curriculum development and is reinforced by our belief that we have inherent genius embedded within each of our communities. When using IGbD, teacher designers work alongside community members to determine community core values, essential questions, enduring understandings and year long themes associated with community cultural values and milestones. By centering the community’s core beliefs and values, the Indigenous Science Curriculum Initiative may assist in uplifting that which is essential to who community members are from a holistic stance. The IGbD process begins with the target outcome (community core values, essential questions, and enduring understandings) and works to continue scaffolding and building curriculum around culturally relevant big ideas.

The Indigenous Genius by Design framework operates according to a theory of change, delineated below:

- There is inherent genius (protocols, knowledge, skills) in Native communities that should drive original curriculum design.

- Community-led design ensures alignment to community desired results.

- There are existing, research-proven practices in designing original curriculum that many teachers and instructional leaders have mastered.

- A, B, and C combined make for community-led, Indigenized learning for students and comprehensive, cohesive, backward-designed curriculum.

- Centering the expertise and autonomy of expert, teacher-designers increases buy-in AND high quality, immersive professional learning of a master curriculum by a non-teacher-designer increases the likelihood that the curriculum is used and used well.

Community Led Design: The curriculum design work in the Indigenous Science Initiative has been driven by a process of Community Led Design. Community Led Design is the purposeful and invaluable process of including Community Members and Knowledge Keepers in the processes of dreaming up curriculum focus as well as providing feedback on drafts of curriculum materials. A wide network of educators and knowledge-keepers from Indigenous science-based fields was invited to participate at the initial convening of teacher designers (with representatives from different Pueblos, Navajo Nation, Northern and Plains Nations, and Indigenous allies answering the call). From there, snowball sampling and continued wide-net focused sampling was used at future convenings. We looked for people who represented both academic knowledge with experience in school settings and organic intellectuals whose scientific cultural knowledge is deep and multi-layered. The engagement of community participants started with building relationships and inviting their voices into the work of the teacher designers. There was also a fair amount of opening the space for discussion from the deep, nation-specific Indigenous perspectives from each community participant.

Community participants were consulted on curriculum topics and themes that needed to be elevated and those that needed to be more peripheral to the design process. Teacher designers engaged in conversation and sought feedback at each step to gauge levels of appropriateness for curriculum choices, to ask for help in guiding the connections to more localized content for nation-specific ways of knowing, and to help guide the ways that Indigenous knowledges (both in broad terms and Nation-specific terms) were being applied to the conceptual frameworks of the curriculums as they were developed. These deeply engaged, rich conversations were steeped in land-based, historical, and culturally based practical and conceptual understandings of the world and the relationships between humans and all living things. In addition to the process of Community Led Design, the project planning team began the development of a Community Advisory Group in spring 2025. The Community Advisory Group convenes with the express purpose of providing feedback on Indigenous Science Initiative project components, including experience planning, curriculum and curriculum materials, and other topics as needed, including elevating Indigenous perspectives in science education in New Mexico and beyond. The Advisory, in its initial meetings, has already provided significant support to the project, including providing important insights as to the history of Indigenous Education and resources for thinking about data sovereignty.

Teachers as Designers: Seven educators were recruited and applied for the role of Teacher Designer in the Indigenous Science Initiative. Teacher Designers are tasked with the nuanced process of building curriculum that reflects their own expertise, experiences, and context, as well as the process of Community Led Design. Designers work in groups of 2 or 3, collaborating to create materials that build from multiple skill sets and can be used and adapted by a wide variety of potential users. Additionally, designers participated in both Zoom workshops and in person convenings with the purpose of engaging consistently in a culture of critique through the design process. Designers, who are practicing educators, alongside their students and community members, are the breath and life of this Indigenous Science Initiative. Their creativity and brilliance is what we hope to share through this curriculum for other educators and students to experience, adapt, and localize.

This work is a part of a larger story: The Indigenous Science Initiative work is part of a deep history of Indigenous curriculum. We seek to add to the great history and tradition of Indigenous Science through this work. The work we have learned from, are inspired by, and seek to be in conversation with is too great to include in these pages alone. However, some projects and thinkers that have inspired this work include:

- Indigenous Wisdom Project through the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center

- Native Lit Project through the NACA Inspired Schools Network

Additionally, as the work has progressed, the ISI team has compiled many different kinds of resources to reference when writing and designing. The ever-evolving document can be found here: IS Project_Supporting Resources for Designers.